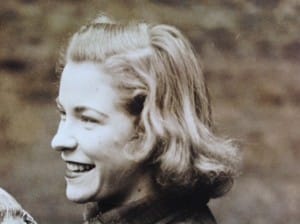

Rosemary Julian Harris, shortly after this experience.

Note: This story was written by Rosemary Julian Harris, prior to entering the Royal Academy of Arts, during the month of October, 1936. The content is from a written notebook of 41 pages, presumably written during the week in which she worked as a pavement artist. The story covers four days, however the first day includes some inconsistencies in terms of setting up two locations. It is possible the first day is actually two days, but appears below as was written in the original story. Rosemary Julian Harris won the Feodora Gleichen sculpture prize at the age of 19.

Pavement Artist, London, October 1936

I have lived in the country most of my life and I began to think that I would like to go to London prior to starting my sculpture course at the Royal Academy of Arts, to see what made it tick.

My mother always said London was a “golden city” with theaters and high life. I am not particularly interested in that sort of life, but am hoping to go to the Royal Academy of Arts in due course. My sister, Deseree, is a student at the London School of Economics, so I was able to stay with her in Bayswater.

Having always been interested in pavement artists since I was a child, seeing old men drawing seascapes and such like, I thought I could do more interesting things with animals and activity. So I have decided to go to Hyde Park Corner, an interesting place with all sorts of traffic, dray horses coming up the hill, and a hospital opposite where I can take my earnings, if any.

I set off by tube first and when I arrived I asked a policeman if it was OK that I set up my pitch. He said “yes” as long as I cleaned up at the end of each day. So I sat down with my crayons and a sack to sit on and started with a picture of lambs skipping about, then horses, then dogs and cats and so on. About six pictures and then I sat down, to rest my knees, and waited for action.

Most people just walked by, some looked a bit surprised but were too busy going to work to stop to speak. It was a fine day with autumn leaves coming down, and no rain, for that would have been the end and a wash out!!

I brought some lunch, which I could eat when I felt hungry.

As the day wore on more people spoke. It was very interesting watching the world go by. One old man came to me with some tips on screeving – as he called it – being a screever himself and told me the best places to strike a pitch. I preferred where I was.

Not many of my friends came to see me, but those who did said I looked rather pathetic.

I don’t care!

I think my appearance caused a great deal of interest. It needs a very brazen mind to walk about London in corduroy trousers. To keep my self possession I convinced myself that I was a girl pavement artist dressed exotically and had a right to be stared at. This ruse was so successful that I felt quite hurt if people didn’t give me a second look.

On arriving at Marble Arch I walked around it once, looking for possible sites, and then went up to a policeman to ask him where I could pitch. He was very short with me. “No Pavement Artists allowed here. If you must go anywhere the Embankment is the place for the likes of you. You can’t come here.”

As I was speaking to him an old lady of the poorer class, possibly a bit weak in the head, shouted at me “Oh put a skirt on ye, for goodness sakes do, with them things on you’re neither woman or man; wear a skirt like a decent body.”

I knew it was hopeless to answer back so I walked along the park railings as fast as I could, she shouting at me ’till I was out of earshot. It was a very discouraging beginning. Prospects that had looked so rosy when I started now seemed to be covered up by London’s murk and grime.

I walked along the empty pavement with Hyde Park Corner vaguely in mind. I walked what seemed an awfully long way, and eventually came to a park entrance, where there were two policemen on point duty. One asked me if I had lost my way; I certainly felt lost. I explained to him that I wanted to be a pavement artist and was aiming at Hyde Park Corner. He went to discuss me with his colleague who came up to me with the traditional “Here, what’s all this about? Want to be a pavement artist? How old are you?” I said “Nineteen”. “Well you ought to be old enough to know what you want so I can’t stop you. Go straight across the park and you’ll come to Hyde Park Corner!”

So I set off. The park was very empty as it was quite early in the day. Hardly anyone else was walking. The only people in sight were a few sinister looking men lurking about under the trees. They had the effect of making my fast walk develop into almost a run. The park seemed to be endless, but eventually the gates loomed into sight. By this time I had developed a most convincing limp due to a blister on my heel.

I saw another policeman in the distance and headed for him. I asked him where I could pitch and what to avoid, and he told me anywhere outside the park gates so long as I didn’t select a bus stop or cause an obstruction. This sounded simple.

I took for my pitch a site between a bus stop, a taxi cab rank and public lavatories. A very strategic position. I asked an old lady at the newspaper stall and she said screevers often came there, she didn’t know whether they were allowed to or not.

I thought I would trust to providence and settle down to draw.

With the sack I roughly swept the paving stones I was to work on and then kneeling on the sack I commenced to draw. From that moment my depression left me and I really began to enjoy myself.

My subject was animals, horses, dogs, lambs, penguins, etc. I roughed the drawings in chalk first and then went over them in crayon afterwards. I had my back to the traffic on the pavement, in fact was quite oblivious of it, until I found coins were being thrown down. So I produced a beret for them to aim at.

Incidently it is quite extraordinary how many people seem to be unable to throw a coin into a certain area, when standing directly above it.

I had just finished one picture and was starting the next when a gruff voice behind me said “Well?” I looked up and was horrified to see an enormous policeman standing over me, at least he seemed enormous from my worms-eye-view of him. I stuttered something incoherently, but he only said, “This is your first day? Well don’t leave too much in the hat or you won’t get any more.” and walked on. My relief was terrific, and the pavement might have been paved with gold instead of the coppers and small change that had found their way into the hat.

I went on drawing with renewed enthusiasm, many passing by came up to watch me. Some said encouraging things to me. The feminine part of my mind began to respond to the flattery and admiration. I was becoming conceited. When some cameramen took up their stand near me I took it for granted I was the object of their study. (Was I out of the ordinary in worthy of fame?) The answer to this came when one of them said “Excuse me miss. Would you pose in front of the drinking fountain? We were sent to photograph it but a figure with it would give it scale.” I shook my head saying, “Sorry, I must get on with my work.”

An ugly stone drinking fountain, a monstrosity, which had hitherto escaped my observation. I knelt down again, finding myself half blinded by the dust arising from my castles in the air having crashed to the ground.

As I was finishing my last drawing, a black cat with white paws jumped down through the pailings out of the park and came up to me greeting me like an old friend. It must have been my lucky day.

Having done a good two hours work and it being long after lunchtime I arranged my sacks as a slight protection from the pavement and sat down, a relief from kneeling.

The cat came back and curled up on my lap, purring like a mowing machine. My hands were hardly recognisable under a coating of pavement dirt and crayons. I tried not to think of all the various germs I was swallowing as I ate a roll. When I had finished my meager meal I was able for the first time to look at the people.

There were many catching and leaving buses. Those who gave me money were not the owners of silver fox furs and cigars, but rather the elderly and middle aged ladies of the middle class and well-to-do businessmen. Several asked me why I was doing this, from necessity or as a joke. I said it was neither but for experience with the hope of opportunity.

My attention was attracted more towards some people than others, especially if passed more than once. In this way I noticed a young man, obviously an artist from his green slouch hat and long hair, to his paint stained plus fours. He had a striking face; a trifle effeminate, but interesting in its seriousness.

Having passed me about four times he stopped in front of me and said, “Do you pose at all?” I said I didn’t being only in London for a short time and during that time working on the pavement. “But I must paint you … I must paint you. I must paint you!” He spoke as in a daze reminding me of a gramaphone needle which had hit a groove. I said it might be managed, if only to give him a mental jog.

This was successful and he gave his address and left me with, “You will come, I must paint you!”

Soon after this my friend the policeman came up and asked me how things were going.

“I’ve been having a spot of bother over you,” he said. “One old dame came up to me, in a proper sour temper she was too. Said you were a disgrace to your sex and oughtn’t to be allowed. What you needed was a good smacking, couldn’t I give you one? Well Madame, I said to her, why don’t you talk to her yourself? It’s no good giving me the dressing down, I can’t tell her to move. She’s doing no harm, not obstructing or anything. So then she changed her tune and said ‘look at those daubs she’s drawn, if she can’t do better than that she shouldn’t do anything at all’. So I said if I could do anything half as good I’d be damn proud of myself. So there you are miss.”

I thanked him very much and he stayed talking with me. He had a week on that beat and was quite pleased to find someone who wasn’t complaining about something or wanting to know how to get somewhere. He was quite the ideal policeman, a round cheerful face, serious but for his eyes which were full of humour. A small moustache and inclination to double chin. Tall yet his uniform was a collection of convex curves. A north country accent and strong sense of humour completed the perfection.

The only other charity seekers were two young street musicians who could only perform when the eye of the law was turned elsewhere. One had a banjo and sang and accompanied his own songs. The other one carried the banjo case. He told me he had an accordian but at the moment a pawn ticket had taken its place. They were blackshirts – one had a black jersey – the other blue. I asked him where his symbol was and he showed me a badge on his lapel. “It only cost two pence cheaper!”

They imparted to me the cheerful information that if I worked for long I would literally wear my fingers to the bone, rubbing the crayon in. I would also probably get pneumonia and rheumatism. I said I didn’t know about that but I seemed to be successfully working up for housemaid’s knee, having worn a hole in my trousers.

“Pavement seat” seemed a probability also, if I sat there much longer. They said they were going to America when they could and I wished them luck, they deserved it.

The policeman didn’t like them, “Don’t you believe a word of it” he said, “They’re real rascals.” Have they been playing when I was out of hearing? Had to admit they had, I am so bad at lies.

An old musician passed me – one of the old school, with bowler hat, long straggling hair and moustache, and a battered coat and tight trousers – clasping his best friend, the violin. I nearly wept when he threw me a penny, which was worth a pound to him, surely. This so depressed me I nearly threw up. What I did not want was misplaced pity. That is when I decided to do it for charity.

Several old ladies stopped and talked to me, causing me several minutes of suspense, as I expected each one to give me the promised smacking – but the majority were very kind. The general impression seemed to be that I was very brave, though I don’t know why. It only necessitates obtaining the right atmosphere to start with, the rest came naturally.

One young man with a black slouch hat – but not in other respects artistic looking – came and asked if I worked at the Slade School. Apparently he himself was a secretary, not an artist, but his sister worked at the Academy School of Art, so he claimed to know something about it. He asked me if I had ever been to a certain pub called the Fitzroy, frequented by artists and their following. As I had not, he suggested that he should take me some evening. I realized that this was being “picked up” but as it did not come into my romantic expectations, I refused. I thought it would be better to fly higher (or lower as the case may be) or not at all for a mere secretary.

My adopter, the cat, decided to leave me and disappeared as rapidly and completely as it had come and with it I imagined my luck would go too – but not entirely. While I was meditating, I noticed another artist looking at my work. He was of middle age, with the traditional black slouch hat, but otherwise not so exotic as the previous one.

He told me that he had seen my work from the top of the bus as he had passed. At the next stop he had alighted and hurried back, afraid I might have packed up. He did portraits etc. in pastel himself and seemed to think my work was promising. I explained my circumstances to him and he was interested and asked me to come and see him at his studio. I must have looked rather dubious for he hastily added, “I’m sure my wife would be thrilled to see you. She is always willing to help any artist.” I thought this might be so, or might not. However he gave me his card, and I promised to come and look him up sometime.

It was beginning to get dark, everybody having gone home to their tea and there was not much more financial profit to be had, so I decided to pack up. The policeman had told me that I must wash off all my work before I left. This I did but it seemed a waste that the work of a morning should be washed away in a few seconds. However one must take the good with the bad and as I had the good in my pockets I had nothing to complain of.

I had heard that a screever made on average half a crown a day. I thought I had made more than that but apart from the weight in my pockets I didn’t know how much. I was amazed and rather horrified to find I had accumulated over a pound. About eight shillings in coppers and the rest in small silver, several shillings and one half crown. That completely decided it. I should do it for charity in future.

Part of the original writing of the story.

NEW DAY

The following day I went into the hospital and asked to see the secretary. I was told to wait and was shown into one of the offices. The typists came in and out, they all had streaming colds and I knew I would have one sooner or later.

I waited for nearly an hour and at last my patience gave out. I explained that I must get to work as all the best business was done in the morning, before people had spent their money. I was just going when the secretary came and I explained to her that I was a pavement artist and was collecting money for the hospital; could I have a collecting box? However she explained that noone is allowed to collect openly for the hospital except on rose days etc. This was rather shattering.

I decided to go to the same patch again as I knew the policeman and it certainly seemed a successful place, unless I had just had beginners luck the previous day.

I wanted to think of a notice but I was not allowed to mention the hospital, it rather limited me. I wanted the public to realise I was not what I appeared. But what was that? Not a tart as I had no make-up at all on, then it must have been that of a rather pathetic figure, that of a young girl in very shabby clothes; a sight guaranteed to rend the average heart string. So I wrote beneath the beret the words “Not for myself”. Of course many people asked, “Well who is it for then?” so I explained.

One old lady, when I told her it was for the Hospital, said that of course she herself did not believe in Hospitals. Where did all their money go to anyway? She knew for a fact that the London bus drivers themselves contributed several thousands towards it. Why didn’t I give money to some really deserving case? I realised it would not have been tactful to argue with her, so I meekly smiled and thanked her.

The policeman came up again to talk with me. I asked what I should draw and he jokingly suggested himself. I thought I had better not do quite that so I did a little white dog wearing a policeman’s helmet. This pleased him immensely and he kept on bringing up his colleagues to admire it.

One kindly old woman passed me for the second time, I remembered her by her unusual clothes (the rag bag variety) and her stockings, which ran endless spiral races down her legs. She beamed at me with a friendly, “How are you getting on dearie?” I said I was getting on quite well, thank you. “That’s right dearie, good luck to ye!” A seemlingly trivial incident but a very pleasing one when you are sitting alone on a cold pavement.

The taxi drivers from the nearby rank would come up and talk to me sometimes. One cheerfully told me that if I didn’t get a cold in my kidneys it wouldn’t be his fault that he hadn’t warned me! I got quite a lot of money from people hiring taxis, as they could afford silver.

A young girl artist came up to me and said she had often thought of doing a screeving job but didn’t know how to set about it, so I told her what little I knew about the rules and regulations. She had thought of a pitch near Burlington House but I told her it would be safer to ask a policeman near there. I shouldn’t have chosen that pitch myself, as people coming out of the Academy would probably find a pavement artist rather an anti-climax.

Another elderly lady threw a shilling into my cap and said she liked my work, but it must be a very hard life. I agreed, but I was thinking of the pavement itself.

Of course many dogs passed with their owners – the majority of them running loose, being town dogs presumably. To these the wall behind my pitch seemed to be a dog’s Post Office and many of them came to leave and collect their letters. This was not too good for my art but very good for trade as embarrassed owners came running to retrieve their miscreants, full of apologies which necessitated their putting something in the hat. Quite good trade could be done this way, if carefully thought out.

It was getting near the end of daylight by then so I packed up and took my earnings to the hospital. They benefited by about eighteen shillings, from which I had deducted my day’s expenses, sixpence. They were immensely grateful, and surprised when they heard how I had come by it.

DAY THREE

So far I had been exceptionally lucky in my weather, having had two reasonably fine mild days. This was too good to last and the third day it broke into a typical London drizzle, making the pavement wet and greasy, impossible to work on. However I thought there might be some possibility of a fine interval so I went to Hyde Park Corner and sat in the subway, reading the paper and trotting up at intervals to view the sky.

About half way through the morning the rain stopped and prospects looked brighter, except that I found myself with the first symptoms of the promised cold in the head. I went to my pitch and mopped up the paving stones as well as I could with my sacks.

It was most discouraging drawing as the chalk would not mark well, and the colours looked dead. I managed to get down about four very mediocre pictures and sat down for lunch.

Very few people were out. Then simultaneously the rain and my cold came out heavily. This was more than I could bear, so I washed out what little remained of my pictures and came home. A bad day financially, I only made three shillings and ninepence, which seemed very petty after the high standard I had set myself previously.

LAST DAY

My last day on the London streets was all that could be desired of autumn. Blue sky and gold trees, wind but no rain. Fallen leaves dressed in the season’s newest shade vieing with each other for first place in the mad race to catch up the departed summer.

I drew with renewed vigour and inspiration. While I was drawing, two pressmen from a daily paper came up and asked if I could spare a few minutes and give them a story. I condescendingly said I would answer their questions if they could come back later, but at the moment I was busy working. They were very polite and said they would come back in the afternoon. This gave me a rather satisfied feeling.

My next visitor was an elderly man of the solicitor type, rather forbidding in appearance. He asked me the usual question, for whom was the money if not for myself. So I told him I was doing it for charity and for the experience. He dropped half a crown in the hat and went on without a smile.

My last picture was, in my own opinion, my best. One of a zebra, which looked alive. While I was drawing this, a young woman came up and said, “Excuse me, but do you ever illustrate books?” I told her I hadn’t so far but that I would like to very much if I had the chance. “I wondered” she said, “because I have just written a book of poems about animals and the man who was going to illustrate them for me has been taken ill, so I thought you might take his place if he is unable to do it. I think you are very talented and quite capable of doing it.” I gave her my address and she said she would let me know. This would be a big opportunity if ever it came to anything. I felt very elated.

After this came rather a contrast in the shape of an ex-pavement artist. A typical cockney, very small with fair straggling hair and a few mishaven bristles on his receding chin. He fixed his rather watery blue eyes on my hungrily. He talked to me for quite a long time, shifting his weight from one shabby shoe to the other, and punctuating his sentences with nervous giggles and long drawn out sniffs. He told me he had done some screeving and used to get his chalks cheaper by going to the wholesale dealers and buying the broken ones. Also he said some screevers used bath brick on the pavement first as it made a better surface to work on. Two tips worth knowing!

Until recently he had had a job in the kitchen of some restaurant. I suppose the chef enforced some standards of cleanliness, for heaven help anyone who ate food prepared by him in his present condition. He said he had been kicked out owing to having a cold. An unconvincing story I thought. He rather reminded me of a cold himself, the way he hung around me. I appeared to be engrossed in my work and he eventually left me. A relief, as the pity I felt for him was easily overcome by the nausea experienced when in his proximity.

When I was packing up in preparation for the afternoon’s contemplation of the pavement passers by, one of the taxi cabbies came up to tell me that the previous afternoon, when I had gone home early owing to the rain, two men, aged about twenty five to thirty, who looked like artists, had been inquiring for me, wanting to know what kind of work I did and any particulars about me. Of course the cabbies were unable to give much information, which caused me all the more annoyance at the thought of having missed an opportunity to possible success. But there was still a faint hope that they might come again.

One young man came and studied my pictures for some time before asking, “Well, and where did you learn to draw?” I replied I was still learning, every day discovering some fresh fault in my work. He said he wished he could do half as well himself. This was satisfying but of no great value.

An elderly man stopped before me, and I recognized him as one of my previous patrons. “You remember me I expect,” he said, “I came this morning. I am going to write a little story about you, in memory of my daughter, the sweetest girl whoever lived. She, like you, was always willing to give money to charity. I am not charitable myself but I admire the virtue in others. I am not going to ask your name and unless you want me to know your Christian name, I shall think of you as Betty, that of my favourite niece.” I thought Betty was as suitable as any except my own name, so I left it at that. I also gave my age and a few particulars but I doubt there was enough subject for a story. Then he continued, “I am going to give you ten shillings for the hospital, because I trust you. I could take it to them myself but I’d rather you did. Good bye and success to you.” And he walked away with hardly a smile, merely a polite hat lift. A kind heart very carefully concealed and protected from the outside world by a suit of coldest steel. I must have an honest face, I decided.

The next face to talk to me was no beauty. A man of about twenty five, with terracotta coloured hair, a pink face and broken looking nose, who said he had been a comparatively famous pavement artist’s model. He was well educated and quite interesting. He told me a bit about his life with the pavement artist. They did not begin work ’till eleven am and went on ’till eleven pm to catch the theatre crowd. He had been given the sack because he didn’t work hard enough and was now studying to be a “masseuse” and was very interested in all the different kinds of medical rays.

But most of it was lost on me as he was literally talking above my head. People do not seem to understand that sound never drops, being inclined to rise if anything. So when talking to a person seated on the ground it is necessary to come down to their level to a certain extent, if an intelligent conversation is to be carried on. As it was my part of the conversation consisted chiefly of “what?” but as the majority of mankind is quite content to talk to anybody who will represent an audience these facts are of no consequence.

Screevers and their following seemed to be rather abundant on that particular day. A marvelous combination of gypsey and tramp came up to me, surveyed my work with a master eye, “You’ll do,” he said, which I gather was praise indeed, for he offered to give me the names of some good screevers’ pitches that he knew of. He gave me an almost complete geographical map of London, on the cover of my sketch book. I let him ramble on, and when he filled up all the available space he went off with that trademark shuffle of a confirmed tramp. So now I have the handwriting of a genuine screever to add to my collection of curious.

Very soon after this, one of the pressmen came along. He said the other one who was to write the story had been unable to come but he himself had been given some questions to ask me. He didn’t know much about the job, being a racing journalist with one main ambition, to own a racehorse. I promised to do a portrait of the first Derby winner he owned.

I gave him a few facts and incidents from my experience of screeving, but would not give my name and address. I did eventually, so that they would be able to send me a copy of the edition with the story in it. Incidentally, after I left London I had a very nice letter from the journalist saying the paper wanted to print my name and address, so as this was against my wishes, there would be no story. This was very considerate, I thought, as, having the necessary particulars they could easily have published the story, got the cash and let my feelings look after themselves, which shows there are always exceptions to every rule, even to the characters of pressmen.

While I was being questioned, my friend of the terracotta hair came up and said, “Excuse me a minute, would you mind signing your name for me in case you are some day famous?” He handed me a notebook quite seriously, so I gave him my signature. He must have been one of the optimists who make this world a brighter place!

It was getting late by then and I would soon be leaving the pitch for good. I had hardly seen the policeman that day, there had been so many people talking to me. I had done a sketch of him from across the road. When he came up I showed it to him and he was extremely flattered and asked to have it. But my sketches are too valuable to me to give away so I said I’d send him one on an Xmas card or something. “Would you give me your name and address?” I said, realizing that it was quite a privelege to ask for this of a policeman. It so much more often happens the other way round.

Soon I packed up and washed out my drawings for the last time. I was sorry to part with the zebra for he had served me well. I took my earnings to the hospital and found I had made over thirty shillings, partly thanks to Betty’s uncle.

I made my way back to my sister’s flat in Bayswater, walking, to think about the last few days. I had seen a bit of what London was made of, the good and the bad. And the hospital was a bit better off for my earnings and I was more than ever looking forward to my life as an art student at the Royal Academy in due course.

This story, originally written by Rosemary Julian Harris, was later transcribed by her daughter, Veryan Leycester Roxby, and then by me, her grandson.